A simple way to improve your estimating (and a cool pub trick) – Part 1

Okay I’ll admit it, I used to really suck as a time and effort estimator. I happen to have a business partner who is much better at it than me (hey Peter), and every time I sought a second opinion from him on my estimates, he would almost always make a much less optimistic assessment then me. Of course, Peter was almost always right too, dammit.

So, why was Peter much more accurate with his estimates?

The answer to this question, all one has to do is think back to their teenage years, where they went through that awkward stage where you look back and cringe at the posters that were on your wall and your choice of fashion. For many, this period demonstrates some utterly appalling choices of taste. Mine are particularly cringe-worthy, given that these days I am a bit of a metalhead. My favourite song at the time was Respectable by Mel and Kim. I thought that Karate Kid II was the best film of all time (and that the girl in it was hot). Mind you, my wife has an even more shameful secret. She had a crush on Jean Claude Van Damme! Mwahahahah 🙂

These are examples of a phenomenon I like to call “Teenybopper bias” 🙂

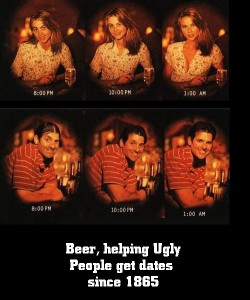

Now, there is a point in telling you about my wife’s secret shame and it isn’t to see her reaction when she reads this (okay, well maybe a teenie bit). These examples of “what the hell was I thinking” are a form of cognitive bias that took place at the time the opinion was formed. In terms of teenybopper bias, the root of the bias is likely the same hormones that caused your face to break out with acne and hair to grow in funny places. Another very common cognitive bias that afflicts people whether young or old is good old “beer goggle” bias illustrated below.

There are many, many forms of cognitive bias documented, such as optimism bias, anchoring, hindsight bias and the recency effect to name a few. Now let’s take the final image above and pretend we asked someone at the pub for an estimate on a project at 8pm, 10pm and 1am. I’d be willing to bet that the estimate gets more optimistic on a par with how optimistic the perception of the people in the image above become.

Overcoming cognitive bias

Kailash writes about the risk that cognitive bias can play in project failure, particularly in the perception of risks.

overcoming biases requires an understanding of the thought processes through which humans make decisions in the face of uncertainty. Of particular interest is the role of intuition and rational thought in forming judgements, and the common mechanisms that underlie judgement-related cognitive biases. A knowledge and awareness of these mechanisms might help project managers in consciously countering the operation of cognitive biases in their own decision making.

The essential difference between Peter and myself in our estimating, is that Peter happens to have a much more finely tuned radar to optimism bias in particular. Douglas Hubbard of Applied Information Economics fame, writes about the effect of cognitive bias extensively in his two books and offers a simple, yet highly useful method to quickly improve the quality of estimates which I will explain with an example below.

The great thing about learning about your cognitive biases and the methods for mitigating them, is that you can use it in the pub too. While I don’t recommend this method for picking up members of the opposite sex, it’s a pretty cool icebreaker.

Thus, I will demonstrate how to improve your estimating accuracy by a mythical pub conversation. Imagine you are onto your third beer…

- Me: “How many SharePoint developers worldwide own a yellow car?

- Them: “What the…I haven’t the faintest idea!”

- Me: “Well, I can understand that, so let’s do an estimate. Give me a range that the answer could fall in, that you are 90% confident with.”

- Them: “I still can’t give you an estimate, I can’t possibly know something like that.”

- Me: “Well, could there be a million SharePoint developers who like yellow cars?”

- “Them: “Don’t be ridiculous, there would be nowhere near a million SharePoint developers – period.”

- Me: “So you do have an upper bound then, less than a million. Remember this is not about the exact answer, I want a range that you would be 90% confident with.”

- Them: “Okay I get it. I think it is somewhere between three hundred and two thousand.

Note that at this point, we have already made the initial breakthrough. At first the person found it impossible to make an estimate, yet when I related it to something they did have a fair idea of (the thought of a million people), they made some mental associations and realised they did have some idea of limits after all. Thus, by presenting a better frame of reference that they could use to approach the problem, they were able to move from “I have no idea” to a wide range of possible values.

The width of the range reflects the uncertainty that someone has about the answer. The more the uncertainty, the wider the range. Some project mangers hate being given a ranged value because it really mucks up their task or project work breakdowns. As a result, they always want the “ball park” or something that is a single value. I completely understand why this happens, but what these people forget is that an estimation is uncertain by definition. The obvious way to express uncertainty is with a range of values! So asking someone for an estimation and then complaining that it is not accurate enough actually makes no sense. A manager might not like the “width” of the range, but you can’t force someone to reduce their uncertainty just because it doesn’t fit the plan. Unless you provide them with the means to reduce this uncertainty, you cannot and should not try and artificially reduce this range through pressure and coercion.

But despite my observation of the flawed logic of dealing with uncertainty in estimating, a ranged estimate alone is not enough yet. We still have not accounted for the sorts of cognitive bias that I described earlier in the article. So without further adieu, I present a simplified version of Hubbards ‘calibration’ techniques that account for bias. Let’s continue the bar conversation.

- Me: Okay, so you are 90% sure that here are between 300 and 2000 SharePoint developers in the world with a yellow car?

- Them: Yes

- Me: So, let’s make this like the game show “deal or no deal”. If you are right and the answer is within your range, you will win $10000. BUT you have an alternative…

- Them: Ok…

- Me: What if I were to present you with a bag containing 9 red marbles and 1 black marble and offer you $10000 if you pull out a red marble. Pull the one black marble, and you miss out on the money. Do you want to stick to your estimate or do you want to draw a marble?

I’d like readers to think about this before continuing with this article. Make a ranged estimate of the number of SharePoint developers worldwide who drive a yellow car, and then decide whether you want to stick to your estimate or take your chances with the marbles.

(Cue game show music where you have 10 seconds to decide with a little ping sound at the end.)

The suspense is now killing you I am sure. Want to know the correct answer?

Find out after this short commercial break (game show speak for wait till part 2 of this series 🙂 )

Thanks for reading

Paul Culmsee

Oh darn. Now I am on the edge of my seat and excited to see how you break down the estimation process further.

Is it a tune in next week? Or undefined time for the next article? 🙂

Richard Harbridge

Brilliant and entertaining exposition (as always). Great stuff!

Regards,

Kailash