Root Causes of Communication Fragmentation: Organisational Culture

This is the second article in a series of articles which examine factors causing the sort of organisational inefficiencies that lead people to use products like SharePoint. My first article in the series examined individual learning and behavioural styles and their impact on communication and how those same learning and behavioural styles still manifest themselves in collaborative tools and informational architecture.

We now turn our attention away from individuals and look at the collection of individuals known as the "organisation". In the first article, I lamented the fact that it seemed no empirical study had even been performed to determine the relationship between behaviour/learning styles and specific collaborative tools/techniques. Fortunately for me, in writing this second article, organisational culture has long been recognised as just about *the* most critical factor in organisational success. What that essentially translates to, is that there is an absolute *plethora* of research on the topic of the influence of organisational culture in knowledge management. In writing this article I had a severe case of information overload but fortunately found exactly what I was looking for.

Knowledge management in academia

Academic papers tend to be pretty dry reads. Researchers, surprise…surprise, write papers to be read by other researchers. Any time you delve into academia to look for answers you have a lot to read and digest, and need a strong jolt of caffeine to keep you going.

Combine that with the fact that the term "Knowledge Management" suffers from rampant buzzword abuse in the same way that the term "Governance" does. This abuse reflects itself in academia where authors are forced to spend pages and pages of their work on defining exactly what they are talking about, whilst making sure that they have demonstrated that they have checked their facts (evidenced by numerous references to other researches).

I ended up finding one particular paper to be very insightful contained within this book:

and in particular, this paper/chapter with an extremely long title…

*Paul takes a deep breath*

"An Empiric Study of Organizational Culture Types and their Relationship with the Success of a Knowledge Management System and the Flow of Knowledge in the U.S. Government and Nonprofit Sectors" by Juan Román-Velázquez, D.Sc.

What a mouthful that was!

Credit where credit is due though, this is a terrific paper and I am going to barely paraphrase it here. But I encourage anyone who wants to ensure that organisational culture issues have been given due consideration in their planing to read this paper. Despite being oriented to government and non-profit organisations, there is a lot of good conclusions to draw from.

Velázquez sets the scene by explaining that public, private, and nonprofit enterprises must survive and thrive in an environment of shrinking distance, complex interdependencies and increased uncertainty. Unsurprisingly, the use of knowledge management (KM) is rapidly growing and tools like SharePoint are commonly used in this area. Velázquez has a good definition for KM that

…provides the capability to engineer the enterprise structure, functions, and processes necessary for the enterprise to survive and prosper. KM leverages the existing human capital/intellectual assets to help generate, capture, organize, and share knowledge that is relevant to the mission of the enterprise. Furthermore, the implementation of a KM system (KMS) enables the effective application of management best practices and information technology tools to deliver the best available knowledge to the right person, at just the right time, to solve a problem, make a decision, capture expertise, and so forth, while performing their work. The KMS can comprise formal systems, processes, management directives, and others that, when combined, help generate, capture, organize, and share available knowledge that is relevant to the mission of the enterprise.

Velázquez than makes the key point that I have always believed. I tell clients that SharePoint is 90% head-space. Velázquez argues although motivations for KM may differ between the public and private sector, the *practice* of knowledge management is very similar. Velázquez also stresses the point that "tools" are a small part of the solution.

A successful KMS involves more than just implementing a new technology that can be acquired in a “box”; it requires understanding and integrating its human aspects and the culture in which it operates.

So SharePoint is not a Knowledge Management System – it is merely one of the tools that underpin a KMS.

Where does organisational culture come from?

A widely held view is that the importance of organisational cultural considerations emerged by the failure of many US and European companies to compete with Japanese firms. Case in point? Look at the history of Ford, General Motors and Toyota. In their book, Diagnosing and Changing Organisation Culture (see below), authors Kim Cameron and Robert Quinn make the point that successful companies with sustained profitability and above-average returns leverage their organisational culture as the key factor for competitive advantage.

Organisational culture can emerge in a number of ways:

- It is sometimes created by its founder (e.g. Walt Disney).

- It may emerge over time, as the organization faces challenges and obstacles (e.g. Coca-Cola)

- It may be developed consciously by the management team (e.g. General Electric through Jack Welch).

How important is organisational culture? Consider this quote from Cameron and Quinn.

The point we are illustrating with these examples is that without another kind of fundamental change, namely, the change of the culture of an organisation, there is little hope of enduring improvement in organisational performance. A primary reason for the failure of so many efforts to improve organisational effectiveness is that, whereas the tools and techniques may be present and the change strategy implemented with vigor, failure occurs because the fundamental culture of the organisation remains the same. Consider the studies by Cameron and his colleagues (Cameron, Freeman, & Mishra, 1991; Cameron, 1992; Cameron, 1995) in which empirical studies were conducted in more than 100 organisations that had engaged in total quality management (TQM) and downsizing as strategies for enhancing effectiveness. The results of those studies were unequivocal. The successful implementation of TQM and downsizing programs, as well as the resulting effectiveness of the organisations’ performance, depended on having the improvement strategies embedded in a culture change. When TQM and downsizing were implemented independent of a culture change, they were unsuccessful. When the culture of these organisations was an explicit target of change, so that the TQM and/or downsizing initiatives were a part of an overall culture change effort, they were successful. Organisational effectiveness increased. Culture change was the key.

That quote, I think hits the nail on the head of why so many SharePoint projects fail. To implement SharePoint without any appreciation for organisational culture is simply not smart. If you are dumfounded by the fact that nobody in the organisation is embracing wikis, blogs and discussion forums, stop and think about it. Is this organisation conducive to such technologies?

Fortunately for SharePoint practitioners who have never considered the effect that an organisation’s culture has on the application of collaborative technology, I’m about to make your life easier… In short, the hard work has been done for you.

The CVF model

In the first article, I used the learning style theories of Honey and Mumford and Marston DISC to explain how our individual differences impacted on the means and methods by which we collaborate. They are not the only theories by any stretch. In fact, pretty much anytime anybody puts up a theory or methodology, you will invariably find someone else trashing it by questioning its validity. Likewise, when trying to quantify organisational culture factors, there are many different measurement methods with different theoretical underpinnings. Naturally, each believes that *theirs* is the right way to go.

I just had a sudden thought that maybe the learning and behavioural styles of an individual has an influence on which measurement methodology they might find to be the most useful.

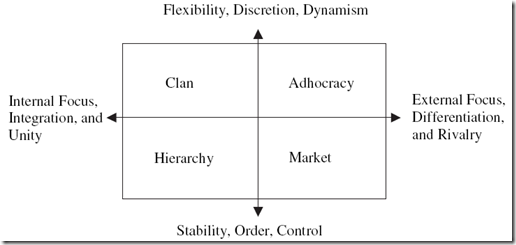

One tool used to diagnose organisations and help executives change their culture is called the Competing Values Framework (CVF). The CVF consists of a framework, a sense-making tool, and a set of steps to analyze and change organisational culture. CVF is best explained with two charts that I have supplied below.

There are two dimensions used in this chart. From left to right, we are looking at "internal versus external" factors such as employee satisfaction, customer service, market share and profitability. From bottom to top, we are looking at the "control versus flexibility" factors such as the internal processes, policies and systems that maintain stability and consistency at one end, and adaptability at the other. Taken together, the two dimensions of the CVF produces four quadrants: Clan, Adhocracy, Hierarchy and Market culture.

Note that it is a very similar dimension based system like Marston DISC. (This is why I like it).

Below I have defined the characteristics of each culture type as defined by Velázquez:

The clan culture: Dominant in flexibility, discretion, dynamism, internal focus, integration and unity.

A very friendly place to work where people share a lot of themselves. It is like an extended family. The leaders, or the heads of the organization, are considered to be mentors and perhaps parent figures. The organization is held together by loyalty or tradition. Commitment is high. The organization emphasizes the long-term benefits of human resources development and attaches great importance to cohesion and morale. Success is defined in terms of sensitivity to customers and concern for people. The organization places a premium on teamwork, participation, and consensus.

The adhocracy culture: Dominant in flexibility, discretion, dynamism, external focus, differentiation and rivalry.

A dynamic, entrepreneurial, and creative place to work. People stick their necks out and take risks. The leaders are considered innovators and risk takers. The glue that holds the organisation together is commitment to experimentation and innovation. The emphasis is on being on the leading edge. The organisation’s long-term emphasis is on growth and acquiring new resources. Success means gaining unique and new products or services. Being a product or service leader is important. The organisation encourages individual initiative and freedom.

The market culture: Dominant in stability, order, control, external focus, differentiation and rivalry.

A results-oriented organisation whose major concern is with getting the job done. People are competitive and goal oriented. The leaders are hard drivers, producers, and competitors. They are tough and demanding. The glue that holds the organisation together is an emphasis on winning. Reputation and success are common concerns. The long-term focus is on competitive action and achievement of measurable goals and targets

The hierarchy culture: Dominant in stability, order, control, internal focus, integration and unity.

A very formalised and structured place to work. Procedures govern what people do. The leaders pride themselves on being good efficent-minded coordinators and organizers. Maintaining a smooth-running organisation is most critical. Formal rules and policies hold the organisation together. The long-term concern is on stability and performance with efficient smooth operations. Success is defined in terms of dependable delivery, smooth scheduling, and low cost. The management of employees is concerned with secure employment and predictability.

I’m sure that just like the previous article, most readers will readily identify the sort of organisational culture to which they belong. Microsoft themselves are a classic case study of an organisation that has attempted to change its culture on numerous occasions with varying degrees of success. Microsoft would like to think that their culture is that of a clan and adhocracy, but the reality is they are very much a market culture. These days they are beaten to the punch my smaller, more nimble competitors, but over the long term they are able to use their formidable market position and financial leverage to succeed. Netscape is a classic example of Microsoft’s market culture succeeding, but you can almost *hear* the rusty gears of the Microsoft culture machine slowly but surely turning as competitors like Google and Linux achieve tremendous success which has been built on very different philosophical foundations.

Having said that, I believe personally that Google is now invariably moving from a strong clan/adhocracy culture starting point to a dominant market culture as well. If you disagree with my assertion then we need to prove it either way. How?

…Enter the OCAI.

OCAI

The Organisational Culture Assessment Instrument (OCAI) is part of the CVF. It is a survey based instrument that allows an organisation to profile what quadrant they are strongest in and to decide if they would be better off by cultivating strengths in another quadrant. There are plenty of reasons why a company might want to do this. Microsoft both succeeded and failed in this regard. They managed to completely out-compete Netscape through Netscape’s own failed execution of strategy, yet they have been playing catch-up with Google for years and still really have not managed to make a dent.

To determine the dominant culture type in an organization, survey questions are group into six "cultural components". The six components are: General Dominant Characteristics, Organizational Leadership, Management of Employees, Organizational Glue, Strategic Emphasis and Criteria of Success.

- General Dominant Characteristics: In general, what does the organisation look like? What the overall organization is like.

- Organizational Leadership: How leaders are perceived in their direction of the institution.

- Management of Employees: The style that characterizes how employees are treated and what the working environment is like.

- Organizational Glue: The bonding mechanisms that hold the organisation together.

- Strategic Emphasis: Areas of emphasis or priority issues that guide the organisational strategies.

- Criteria of Success: Evaluation criteria and procedures to determine level of achievements and outcomes. It is how victory is defined and what gets rewarded and celebrated.

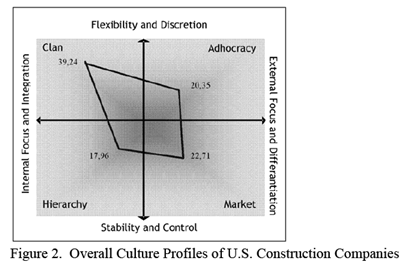

Each question has four alternatives representing each CVF quadrant (A=Clan, B=Adhocracy, C=Market, D=Hierarchy). Individuals completing the OCAI are asked to assign a score to each alternative. A higher number of points are given to the alternative that is most similar to the organisation in question. Results of the OCAI survey are obtained by computing the average of the response scores for each alternative. This can then be plotted as per the example below.

Et Voila! Now we have a much clearer assessment of the culture of an organisation, based on the feedback from the members of the organisation.

Is it worth it?

Geeks who have made it this far through this article are at this point wondering what I am smoking, but rest assured – this stuff is critically important for anybody who is tasked with putting SharePoint into an organisation.

It actually turns out that research using the CVF quadrant has shown that large organisations able to balance their competing values by growing strength in each quadrant tend to outperform other organisations over the long-term. Therefore, the tools and technologies that are put in place to support knowledge management need to also take into account the culture of the organisation in order to extract maximum value from the investment.

Each of the four traits were also significant predicators of other effectiveness criteria such as quality, employee satisfaction, and overall performance. The results also showed that the four traits were strong predicators of subjectively-rated effectiveness criteria for the total sample of firms, but were strong predicators of objective criteria such as return on net-assets and sales growth only for larger firms.

In a following post from this series, I will present the findings of the Velázquez paper which undertook an empirical analysis of KM priorities and critical success factors of many organisations using OCAI.

How would SharePoint look?

In the first article I had a section where I theorised how a SharePoint installation would look like if behavioural types had been taken to extremes. In the interests of consistency, I think it’s good to repeat that experiment in poor stereotyping here:

The clan culture is social networking personified and therefore Facebook style applications are the answer to collaboration and knowledge management. Employees twitter away to each-other and share everything. SharePoint’s "My Sites" are the obvious candidate here, but to a mature clan culture, my-sites are pretty antiquated and almost laughable compared to some of the competing cloud based applications out there. Document libraries? Sheesh! What do you need documents for anyway? Everyone uses blogs, wikis and Information architecture consists of tagging anything and everything. A mature clan culture would very likely utilise 3rd party add-ins like Newsgators Social Sites if they were to make a SharePoint investment.

I actually believe that anyone who considers themselves a clan culture and is putting in SharePoint is really a market culture with a case of rose coloured glasses 🙂 .

The adhocracy culture is essentially every startup company as well as any CEO who describes themselves as "dynamic". SharePoint, in this type of culture, does not have an information architecture to speak of (in the ‘classic’ meaning of that term). SharePoint features will be used as needed and grow over time. If it works, it will be used, if it does not, it will lie abandoned. Anything newly released will be eagerly tried, kept or discarded depending on relevance and usage. Some re-use from learning will take place, but ultimately SharePoint will perpetually be a work in progress with no central governance authority. Most power users will be administrators of their own sites and any attempts to impose centralised order or a governance regime that is based around centralisation and standards will likely fail. Decentralised control for this type of organisation is fine because there is a strong sense of ownership of the knowledge and information.

The market culture would start to utilise SharePoint in a manner that is most in keeping with the literature around features, deployment and governance. Dashboards and KPI’s would feature heavily, as well as workflows that contribute to the ease of collecting performance measurements. Reporting Services integration in particular will fare well here. In a market culture, very little sympathy may be given for SharePoint functionality that is not seen as contributing positively to the business. Additionally, users are unlikely to change for the sake of change or because it is something new and shiny. A market driven culture will implement SharePoint because they see a tangible, quantifiable reason to do so.

The hierarchy culture will implement SharePoint in its most ‘classical’ style. They will naturally make use of site collection, sites and subsites and enforce strict, often complex security boundaries with tight centralised control. Chances are that significant time will be invested into ‘classical’ governance such as forming a committee, standardising on structure and conventions and trying to create a solution that is repeatable with a minimum of rework. Workflows will be very popular, as well as form services as well as document centric collaboration. Facebook style social networking will most definitely not be a high priority, and what’s more, will probably be blocked by the corporate firewall anyway!

Another note: SharePoint out of the box in my opinion is most suited to the latter two organisational cultures. Is it any surprise that a market culture organisation such as Microsoft would produce a collaborative tool that happens to work with it’s own organisational culture? Therefore it begs the question whether an organisation founded on one culture can ever really write the perfect tool for another culture?

Culture based communication fragmentation

Just like the first article, I have painted a pretty stereotypical picture of the sort of SharePoint installation I’d likely see. Some readers (dare I risk suggesting younger readers?) may look at the market and hierarchy culture as old school, representing 20th century organisational thinking. Certainly Linux proves that the clan culture can be extremely successful against the old school guys. But there are many stories of organisations that have had massive initial success, only to get left in the dust once the slower market and hierarchical cultures get their act in gear. One thing hierarchical cultures can do exceptionally well is repeat process more consistently, with fewer defects which ultimately reduces cost. They may not be all that quick at first, but it’s not always about being first to market.

Once again I leave you on an Information Architecture note. Someone who only knows a clan culture will very likely put together a SharePoint solution vastly different to someone who has only known hierarchical culture. The prevailing culture will always win the technology battle, no matter how passionate the individuals are. Even organisational stakeholders in a SharePoint project often make this mistake with the "build it and they will come" approach and think that making the technology available will change the culture . This is both naive and dangerous and has the effect of setting yourself up for project failure.

So, you, as an information architect, need to acutely be aware of the prevailing culture. If your stakeholders give you mixed messages, then perhaps the CVF/OCIA analysis would be a very timely and smart thing to do.

Thanks for reading

Paul Culmsee

This is definitely a good article, and has really perked my ears up on a topic which has been sniffing about but I didn’t give a second’s notice to applying it to my Sharepoint project.

So, I’ve fired in a couple of pages on Organisational Culture in my Risk Assessment… “Make sure it fits in with the guys otherwise it’ll be psychologically seen as change!”.

😀

Please check out our site where the OCAI can be done online. We also have videos and podcasts about organisational culture and the OCAI